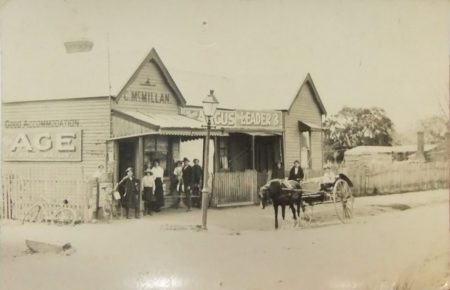

The early 1880’s was an incredible period of growth in Victoria, and not unusually, Melbourne. The need for timber was at a peak from 1881 to 1887, and the opening of the forests in West Gippsland provided a means of getting the raw materials to a hungry Melbourne market. Mills sprung up overnight to quench the thirst for timber, and at one stage the number of mills in Victoria increased from 129 in 1880, to 244 in 1885. Many of these mills were in the Daylesford area, but the West Gippsland forests outstripped the Daylesford output by 1884. Demand was high, and this brought forward investors and speculators, determined to reap some part of the spoils from the forests around Longwarry.

When the sawmillers arrived, it proved to be an economic boost for the region. The timber cutters were happily taking their profits from the forest, but the big winners in this were the farmers who had chosen selections where the timber was to be taken. These farmers had little hope of clearing their land alone, so when the sawmillers moved in, the farmers took a royalty from the sawmillers for the use of their land and sometimes took on casual employment with the timber workers to supplement their income. When the sawmillers moved on, the farmers had cleared land to establish the farm of their choice.

The proximity to the timber from the rail was so accessible that a rail trip from Longwarry to Darnum in 1879 must have been in complete shade, so close was the timber to the rail. As the timber was felled close to the rail line, transport was of little concern for the millers. It was only when new timber was required, and transport (especially in wet times), had become extremely difficult and expensive that an all-weather solution was first mentioned. Tramways were put forward as a lower cost answer to the problem. So began a series of rails into the forest to harvest the precious timber. However, the tramways were to become a key issue of the time.

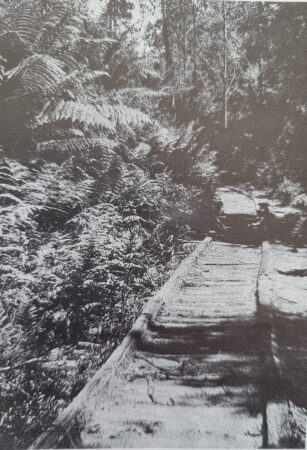

A typical log tramway leading into the forest, possibly to Freeman’s mill

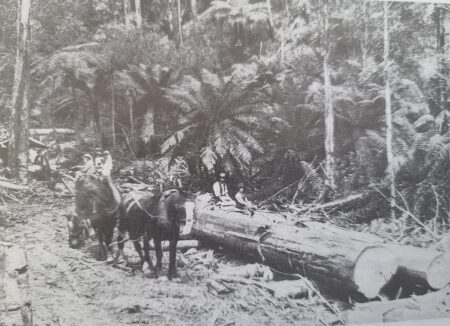

Prior to the tramways being built, much of the logging process involved horses or oxen dragging the logs through a series of “trenches” called snig tracks, guiding the logs to the saw mill. Sometimes, if snig tracks could not be used, the logs were carried on a system of cables, called a “high lead” across gullies and over tree tops. While this system worked, a more efficient transport system was required.

Horses being readied for attachment to the logs. Note the logs under the main cuttings. These were used like a wheeled system until the logs reached the “snig”

Picture courtesy C McDermid collection

Timber tramways were a major feature of the forests around Longwarry in the second half of the 19th century. Trees were felled with a broad axe and crosscut saw and moved to nearby mills by winch, horse or tramway. The mills were typically located deep in the forests and the sawn timber was usually moved to the nearest railhead by a steam hauled tram or horses The infrastructure associated with these tramways is astonishing, long, low bridges and extensive earthworks, all built by cash strapped mill owners in the knowledge that they would be abandoned after 20 years when the nearby timber was cut out.

In those days, the timber men lived at the mill sites, with the opportunity of visiting a town on Saturday afternoon and Sunday only. The work was hard, they climbed the tall trees, cut off the top branches, and then the bole was felled with axe and crosscut saw, loaded onto trolleys and transported to the mill.

Community tramways

While most agreed the need for tramways was apparent, the question of “who would pay for them” was the cause of much discussion, and controversy. The building of “Community Tramways” was suggested around 1880. Government representatives at the time were in full support of the idea “in principle” but were not forthcoming with the funds required. One such community tramway was started by the Shire near Warragul but was quickly ceased when residents from other parts of the Shire (who would gain nothing from the tramway) but were to bear part of the cost, threatened legal action against the Shire.

Many residents were told of the benefits that the tramways would bring. Residents were assured that the tramways would not only service the mills but would also be used to deliver supplies to outlying areas. While this was in fact true, the sawmillers rarely made any arrangements for the movement of supplies. Their main reason for the tramways was to clear the forest and make a profit. The proposed tramways to serve farms were openly publicized but never built.

The only semblance of a community tramway was at Bunyip. The man responsible for draining the Koo Wee Rup swamp, Carlo Catani, diverted funds from the drainage to the building of a tramway near Bunyip to service the residents. This tramway however was little more than a construction tramway and not really a community facility.

So, the Community Tramways scheme was shelved, and the sawmillers were made to finance their own lines into the bush. Hundreds of kilometres of tramlines were built to service the timber industry as demand soared. Mills popped up at a tremendous rate, with men wanting to make their “fortune from the forest”. Some of these men did indeed make a success of it, others lasted little more than a year or 2 before giving up and moving on.

The community tramways scheme was a good idea “on paper”. A lack of Government backing, and resident dissent saw them confined to the rubbish bin of history.

The tramways idea survived and flourished over the next few decades.

Acknowledgements:

Most of the material mentioned is from Mike McCarthys book “Settlers and Sawmillers. We thank Mike for the use of his works.

Additional information is from “Australian Mountains” Website.

Thanks again Longwarry &District History Group. Another interesting piece of our history.

I will pass on your thanks.